Xiaoba Translator | Barcelona s "leverage" road to self-rescue: the thorny road to rebound from the financial bottom

Out of the financial abyss, Barcelona staged a thrilling "leverage" self-rescue. Selling off assets and overdrawing the future is just to retain competitiveness. This thorny road is a desperate gamble, and it is also a difficult survival for members-only clubs in the Jinyuan era. The Athletic writer Chris Weatherspoon tells this story.

Barcelona’s downturn seems to have finally turned a corner.

They regained the La Liga championship last season and won the trophy twice in the past three years, eliminating the haze of three consecutive years without a championship at the beginning of this century. The Champions League also reached the semi-finals for the first time in six years. Despite losing to Real Madrid in an away game last weekend, Barcelona has won four consecutive El Clasicos in all competitions. This team finally regained its competitiveness.

The football world has always been like this: struggles on the field will lead to restlessness off the field. Barcelona's off-field drama in recent years has been full of ups and downs - costs and debts have soared, and a variety of shady operations and financial means have been dazzling. It even spawned a new word in football: "leverage".

These levers form a key part of Barcelona's financial picture, even if some of the operations were initiated years ago. They have had a profound impact on Camp Nou's finances, as have ongoing renovations that have seen the team say goodbye to its legendary home.

In recent years, it is almost impossible to sort out Barcelona's financial situation. Its complexity is like fighting a hydra - as soon as one complicated transaction is clarified, two new ones appear immediately. When the Catalan giant announced its financial results for the 24/25 season in October, it claimed to have achieved "all-round economic recovery and operational efficiency improvement."

But as always, beneath the rhetoric, the truth is often more subtle.

Barcelona's situation has indeed improved a lot compared to a few years ago. "Recovery" is the right word, and leverage has its uses.

But where will these operations take Barcelona? The answer is complex. To answer that question, we have to go back to how a club that was once one of the richest in the world hit financial nadir.

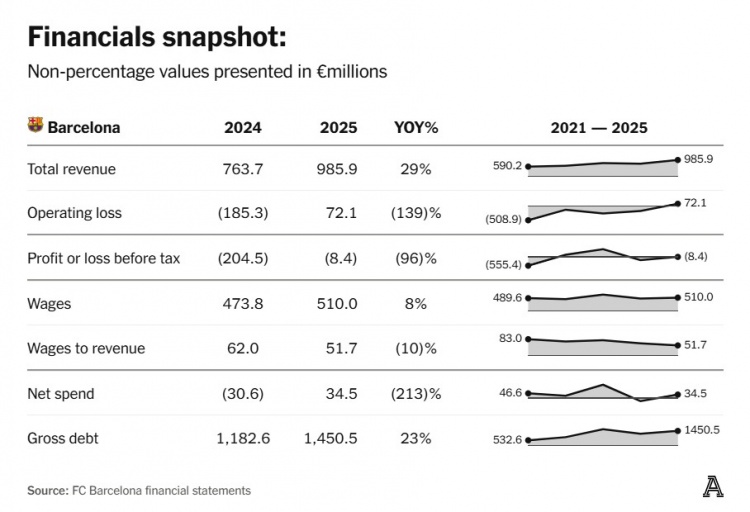

Barcelona Financial Overview Table

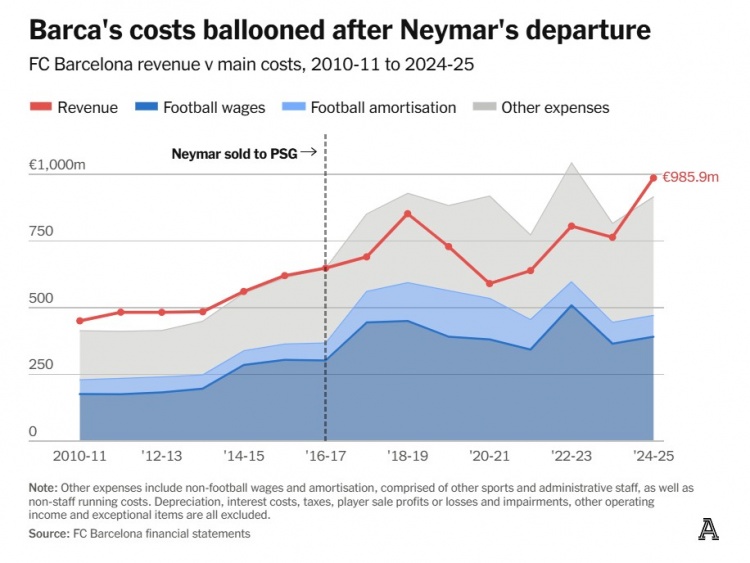

On August 4, 2017, 25-year-old Neymar smiled brightly at the Parc des Princes in Paris, holding a Paris Saint-Germain jersey. After four seasons with Barcelona, the Brazilian striker chose to start a new life in Paris. As a price for Neymar's departure, Barcelona received 222 million euros, which is still the highest transfer fee in football history.

Neymar's transfer seems to confirm the financial strength of his old club. When he left, the club behind him had been profitable for six consecutive years, with wages accounting for less than 60% of revenue, and revenue growth was steady: 164 million euros in three seasons, an increase of 34%.

Barcelona’s revenue of 648 million euros at the time ranked third in football, less than 30 million euros behind Real Madrid and Manchester United. No other club has surpassed the 600 million mark. Now, they hold the highest transfer fee in history, which is the icing on the cake.

However, Neymar’s transfer does not bring continued prosperity, quite the opposite.

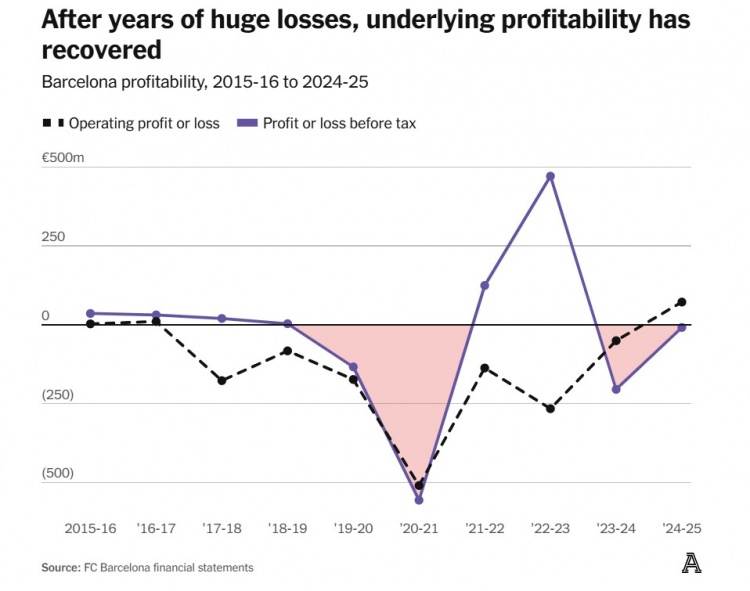

Barcelona made a profit again in the 2017/18 season, but considering this record transfer fee, the scale of the profit is negligible. The club recorded a pre-tax profit of 20.1 million euros, but this was after taking into account profits from player transactions of more than 200 million euros. Operating performance dropped sharply, from a profit of 10.5 million euros in the 2016/17 season to a loss of 176.8 million euros (see the figure below).

It wasn't until last season that they returned to operating profit.

Barcelona's underlying profitability has now recovered

This decline can be largely attributed to one factor: player spending.

In the seven seasons before the 2017 summer window, Barcelona's total expenditure on player salaries and transfer amortization (the annual cost of transferring transfer fees over the contract period) has always been less than 60%, and only slightly exceeded it once (60.3% in the 2014/15 season). In the 2017/18 season, this proportion soared to 81.3%.

Before calculating other operating costs for a club of Barcelona’s level, 81 points out of every 1 euro are eaten up by player-related costs. And these other costs have historically been high. The club's financial structure deteriorated rapidly.

Instead of using Neymar's transfer fee for long-term investment, they immediately squandered it all, and even made it worse.

When Neymar left the team, Barcelona spent 347.4 million euros on player registration, mainly on new players (see the picture below). The transfer fees of Coutinho and Dembele both exceed 100 million euros. In July 2019, Griezmann also joined with a worth of over 100 million. As of the 19/20 season, Barcelona's player transfer expenditures in the three years have reached 960.3 million euros, with a net expenditure of 399 million euros. Between 2017 and 2019, the team's expenditure on wages and amortization soared from 367.4 million euros to 593.9 million euros, an increase of 226.6 million euros (62%).

After Neymar left, Barcelona's expenses increased sharply.

Expensive signings were naturally accompanied by high wages, but another major event at the time also contributed to the situation: Messi's contract extension.

On November 25, 2017, a few months after Neymar left the team, and before Dembele and Coutinho joined, Messi signed a new contract and will stay with the team until the summer of 2021.

Barcelona’s official announcement highlighted Messi’s new termination clause of 700 million euros, but did not reveal how much the club would have to pay in the next 43 months. More than three years later, the truth emerged after Spanish newspaper El Mundo obtained and exposed contract details.

The figures are eye-popping, especially when Barcelona's financial situation is extremely tight. The contract, reached at the end of 2017 and retroactive to the beginning of the season, stipulates that Messi’s potential total salary in the next four years is as high as 555.2 million euros..

Among them, the Argentine’s salary and image rights contract totals 288.6 million euros, and the contract renewal bonus is 115.2 million euros. The loyalty bonus for staying in the team after February 2020 will add another 77.9 million euros. The rest of the contract is tied to performance, so it is not fully realized, but Messi's estimated total income under the contract is still 515 million euros.

This huge amount of money is shocking enough on its own, and it becomes even more astonishing when combined with the background. From the 2017/18 season to the 20/21 season, except for Barcelona, only two clubs have a total salary expenditure of more than this amount in four years. With the exception of Real Madrid and Atletico Madrid, Messi's estimated pre-tax earnings exceed the combined wages of all employees at any other club in Spain. Sevilla, which had the fourth highest wage expenditure during the same period, totaled 479.3 million euros, which was 36 million euros less than Messi's estimated total income.

Messi did not actually receive all the money during the contract period. He was one of many who agreed to delay receiving large wages to ease Barcelona's financial crisis.

These delayed payments stem from another blow that has hit club finances hard: the coronavirus pandemic.

Few industries are immune, but in football, the richest teams are feeling it the most. The home gate is closed, huge wages are paid, and the club's balance of payments is seriously out of balance.

Barcelona’s matchday revenue plummeted from 174.9 million euros in the 18/19 season to 23.7 million euros two years later. The delayed payment of wages agreed to by Messi and others has reduced the total salary in the two seasons most affected by the epidemic from 541.9 million euros to just under 490 million euros, but the overall revenue reduction of 262 million euros has far offset this part of the savings. Deloitte's 2021 due diligence report shows that player salaries of up to 389 million euros have been delayed, highlighting Barcelona's dilemma during the epidemic.

Of course, late payment does not mean that the bill will eventually go unpaid.

The club's financial collapse, coupled with Messi's application to leave the team in August 2020, eventually led to the resignation of chairman Bartomeu before he was forced to step down in October of that year. The successor is the returning Laporta, who served as Barcelona president from 2003 to 2010.

Laporta took office with a plan to save Barcelona's finances and was eager to place most of the blame on the management team headed by Bartomeu.

In the 20/21 season, Barcelona recorded a pre-tax loss of 555.4 million euros, setting the worst financial record in the history of a football club.

Although Laporta emphasized that "the serious mistakes of the previous management" were the root cause of "Barcelona's worst financial report in history," part of this huge loss was also an active choice of the new management. This season, Barcelona depreciated the player's book value by 160.6 million euros and made provisions of 84.1 million euros related to tax and legal proceedings. Although these expenses were approved by the club's auditors, they also helped Laporta's team present cleaner accounts starting from the 21/22 season.

In the first full season of Laporta's second term (21/22), the club did turn a profit, but there are important prerequisites.

This leads to "leverage".

In its statement to the Court of Arbitration for Sport at the end of 2024, Barcelona stated that after being elected, the current board of directors realized that "liquidating some (club) non-sports assets is the most effective and almost the only way to restore net assets." They said the move was aimed at "avoiding direct impact on members while remaining competitive on the field".

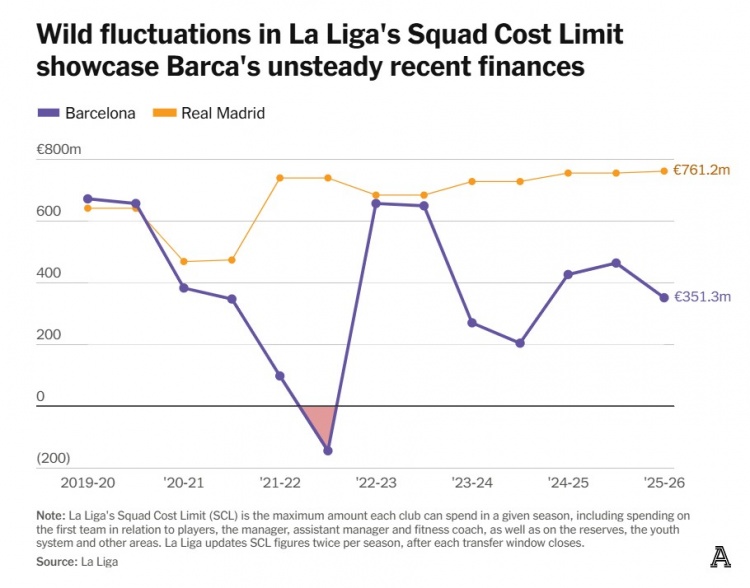

Barcelona not only has to alleviate its overall financial difficulties, but also deal with the pressure of La Liga - its lineup cost limit rules have brought endless troubles (see figure below). The rule is intended to limit clubs from overspending by deducting non-sporting expenses from expected revenue and the remaining amount being the cap on squad spending for that season. The key is that SCL (Squad Cost Limit, squad cost limit) is forward-looking, preventing debt from accumulating by limiting player registrations in advance.

By the beginning of 2022, Barcelona's finances were so bad that its SCL was negative (negative 144.4 million euros). This is obviously unsatisfactory and actually means that they cannot register new players and must significantly increase revenue or cut expenses to break the situation.

The dramatic fluctuations in the cost cap of La Liga teams highlight Barcelona's recent unstable financial situation

After the epidemic, neither able nor willing to significantly increase membership fees, and at the same time unwilling to sacrifice competitive strength, the club finally decided to sell off long-term assets in exchange for short-term blood transfusions.

If this sounds irresponsible, it should be pointed out that Barcelona, like Real Madrid, is more limited than most giants in getting out of financial difficulties. For example, Real Madrid will sell part of its interest in the renovated Bernabeu operating business in 2022 in exchange for 360 million euros in 20-year profits.

The membership-based nature and the resulting limited capital injection capacity mean that the two clubs must operate steadily. And for much of the first two decades of the 21st century, Barcelona did. Between 2003 and 2019, they only lost money in two seasons, with a cumulative net pre-tax profit of 228.8 million euros during that period.

When the situation takes a turn for the worse and the epidemic worsens, Barcelona’s response options are far less than those of clubs such as Paris (owners’ investment amounted to 671.4 million euros from 2019 to 2024), Manchester City or Chelsea. Relying on their past substantial capital injections (and the expectation of continued blood transfusions if necessary), the latter two still spent a combined 468 million euros on signings when global football was struggling due to empty stadium operations in the 20/21 season. Perhaps coincidentally, the Champions League final that season was Manchester City versus Chelsea.

Barcelona could have cut back on player expenditures like a cliffhanger, but in an era when they need to compete with oil capital and national wealth for the European arena, it is reasonable for them to choose to prioritize short-term gains over long-term planning.

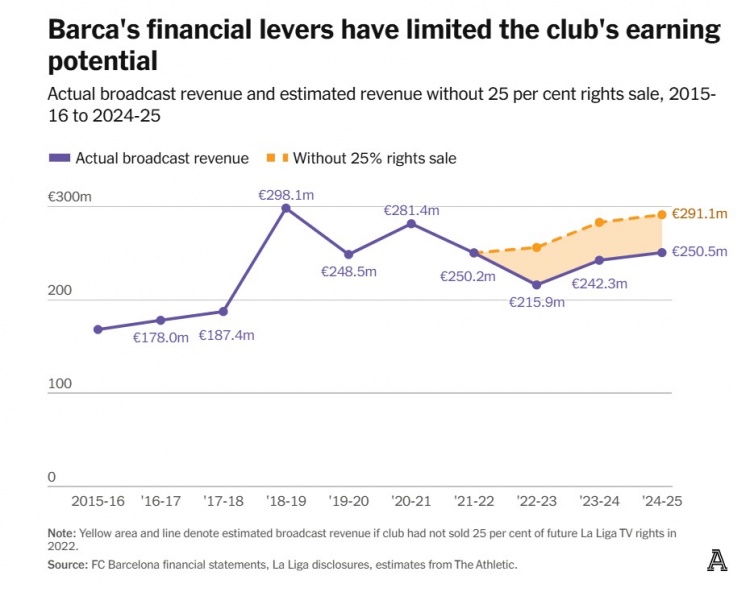

The first round of leverage will be launched in June 2022, and Barcelona announced the sale of 10% of La Liga's television broadcast share for the next 25 years. The buyer, American investment group Sixth Street, paid 267.1 million euros and a few weeks later bought another 15% interest for 400.4 million euros.

In total, Barcelona gave up 25% of its domestic broadcast revenue over the next 25 years in immediate exchange for 667.5 million euros in cash. The first transaction will be included in the 21/22 fiscal year, and the second transaction will be included in the 22/23 fiscal year..

The cash injection helped offset an operating cash deficit of nearly 200 million euros in the latter financial year. Barcelona has a buy-back option at an unknown cost and can redeem these interests early before the 25-year term. But at the same time, selling means they're giving up significant annual revenue.

After years of huge losses, Barcelona's basic profitability has recovered.

The changes in broadcast revenue are clear at a glance. Last season, the revenue increased by 3% due to reaching the semi-finals of the Champions League. However, the broadcast rights revenue for the 2024/25 season only returned to the level of 2021/22 - that was the last year that Barcelona enjoyed the full La Liga share.

Since the transaction with Sixth Street, Barcelona has handed over approximately 120 million euros in broadcast revenue, accounting for 18% of the leveraged financing amount. Even if the value of La Liga's broadcast rights remains unchanged until the contract expires in 2047, the total broadcast revenue Barcelona will give up will reach 1 billion euros - 50% higher than what it will receive from selling the rights in 2022. In fact, the deal is equivalent to a 25-year loan with an interest rate of 3.5%, and this is assuming that the broadcast rights do not increase in value.

In order to maintain competitiveness on the field, Barcelona invested 162.9 million euros in signings (the highest in La Liga) in the 2022/23 season, mainly signing Rafinha, Konde and Lewandowski. However, La Liga did not fully recognize that the Sixth Street transaction funds could be immediately included, resulting in players that the club had invested heavily in being unable to register.

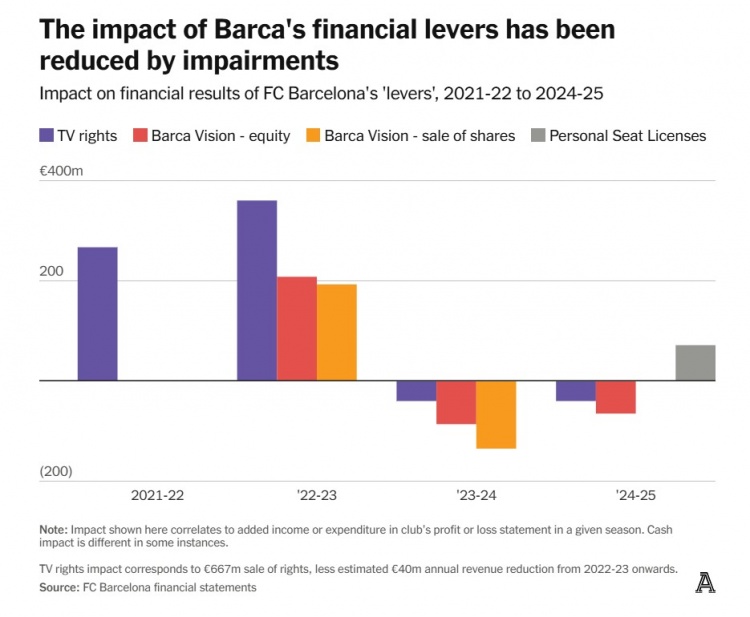

As a result, with the second sale of broadcast rights, two more levers were pulled that season, both related to Barcelona Studio. The entity was established by Bartomeu and focuses on the production of audiovisual content. By 2022, it is regarded by Laporta as a shortcut to a quick bailout.

On July 29, Barcelona sold 24.5% of Bridgeburg Invest S.L. (the entity set up by the club to partially sell Barcelona studio assets) to the blockchain-based platform Socios for a price of 100 million euros. Thirteen days later, production company Orpheus Media purchased another 24.5% stake at the same price.

These two transactions brought Barcelona a net income of 192.9 million euros, and the operations did not stop there. The club still holds a 51% stake in Bridgeburg, but has reclassified it as an associate rather than a subsidiary, meaning a loss of control. Therefore, they can record this part of the equity as current book income without consolidating Bridgeburg's financial statements.

There is no cash settlement for the latter leverage, but with the sale of 49% of the shares for 200 million euros, Barcelona values its 51% stake at 208.2 million euros.

Combined with two equity sales and the disposal of 15% of broadcast rights, these levers created an accounting profit of 801.5 million euros in the 22/23 season alone. La Liga accordingly increased Barcelona's SCL quota simultaneously. This was necessary: Barcelona's wage bill soared to 625.7 million euros that season, setting a club record and ranking third in the history of European football. The increase mainly came from previously delayed salary payments.

La Liga's attitude changed again when it was discovered that Barcelona had only received an initial payment of 10 million euros each from Socios and Orpheus Media for Bridgeburg shares. The two buyers subsequently resold part of their shares to German company Libero Football Finance and Dutch NIPA Capital. Barcelona later sought payment from Libero through German courts.

The impact of financial leverage on Barcelona

The Barcelona studio deal contributed €401 million to the bottom line, but much of it has since been reversed. In the 23/24 season, Barcelona made an impairment provision of 135 million euros for receivables from two 100 million euro equity transactions, essentially admitting that the money cannot be recovered.

Barcelona Studio was so controversial that former auditor Grant Thornton issued a qualified opinion on its 23/24 financial report. what does that mean? In short, the auditors did not accept the valuation of Barcelona's stake in the studio through Bridgeburg. In view of the failure to recover the equity sale proceeds, Grant Thornton believed that the equity value of Barcelona Studio (later renamed Barcelona Vision) was overvalued and needed to be impaired; Barcelona disagreed, so the auditor pointed out that there was a material misstatement in the valuation of the club's accounts. Barcelona refused to recognize the impairment in the 2023/24 season, but made a provision when restating the current year's data in the latest statement.

A new auditor has replaced Grant Thornton. Although it may seem strange that Barcelona would accept a impairment that they had staunchly opposed a year ago, it is important to understand that La Liga's cost control rules are forward-looking. Now that the 2023/24 season is behind us, the negative impact (at least domestically) of the retrospectively recognized impairment loss of €86.1 million, which caused the pre-tax loss for the year to soar to €204.5 million, has been reduced.

Victor Fonte, who lost the 2021 presidential election to Laporta and may run again, recently pointed out that the delay in accruing impairments exposed a "lack of transparency" and was an example of the board of directors concealing losses from members.

The impairment from last season continues. After canceling the plan to spin off the listing of Barça Media (which integrates all digital and audiovisual businesses of the club, under which Bridgeburg and Barça Vision are subordinate), the latter merged with Barça Productions (the entity that originally held shares in Bridgeburg).

This reduces the club's shareholding in Barcelona Production from 100% to 53.4%, and the collaborative management after the merger means that Barcelona Production is no longer included in the consolidated scope of the Barcelona Group's statements. The revaluation of the loss of control, combined with the reassessment of the overall value of Barça's production, resulted in an impairment charge of €65 million for Barça's 2024/25 financial year. Of the 401.1 million euros in revenue recognized related to Barcelona Vision in the 2022/23 season, 286.2 million euros have been impaired.

This blow to last season's income statement was offset by another lever.

The renovation of Camp Nou will eventually add 9,600 VIP seats, which will be sold at a high price. In January this year, the club completed the sale of "Personal Seat Licenses (PSL)" for 475 of its seats. The PSL is valid for up to 30 years..

Essentially, the club sells the rights to use these seats to the buyer for the next thirty years, who can use them themselves or resell the license. Barcelona gave up seat rights in exchange for steady income. The 475 PSLs sold in this round have generated a revenue of 100 million euros for the club.

Of the 100 million euros, Barcelona recognized 71.6 million euros as revenue for the 24/25 season, and the remaining 28.4 million euros were included in future periods (the accounts did not specify the basis for allocation).

To understand why Barcelona’s battle with La Liga SCL continues, imagine that if all PSL income was excluded, last season’s pre-tax performance would be a loss of 80 million euros. This is why the Camp Nou restart is so crucial.

Whether more similar measures will be taken is uncertain.

In June 2022, Laporta was approved by members to sell up to 49.9% of Barcelona's licensing and merchandise subsidiaries. The matter has yet to be resolved, and Treasurer Phelan Oliver made it clear last month that BLM would not sell.

Barcelona's intention to avoid pulling this lever is obvious. BLM’s revenue exceeded 150 million euros last season. The revenue from this commercial subsidiary alone exceeds the latest combined revenue of all La Liga clubs except Real Madrid, Atletico Madrid, Sevilla and Real Sociedad.

In early April 2014, Barcelona members held a historic vote.

More than 27,000 members (accounting for 72% of the voters) approved the "New Camp Nou Plan", which aims to upgrade and expand the home stadium and surrounding areas. In addition to the renovation of the football field, a new Bau Blaugrana pavilion will be built for the basketball, handball, hockey and indoor football teams.

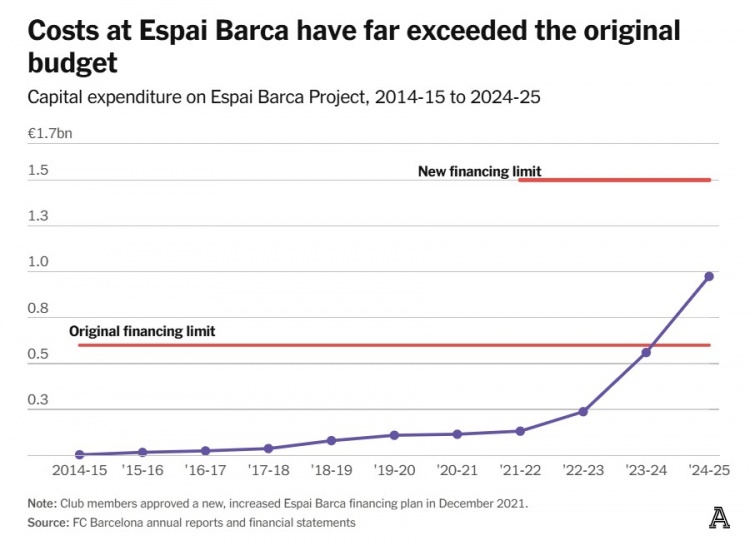

All projects were originally scheduled to be completed within four years from May 2017 to March 2021. The project budget is 600 million euros, divided equally among three parts: 200 million euros in naming rights income from the new Camp Nou, 200 million euros in positive operating cash flow and 200 million euros in bank loans. Yet, nearly twelve years later, the project is still underway and costs have long since spiraled out of control.

The original budget of 600 million euros was abandoned when Laporta returned as chairman in 2021. At that time, there was little progress in the project, let alone completion on schedule. The Cruyff Stadium (home of women's football, B team and U19), which can only accommodate 6,000 people, has been built.

At the end of the same year, members voted again on project financing and passed Laporta's new plan with a higher support rate than in 2014.

The newly approved budget ceiling is as high as 1.5 billion euros, which is 1.5 times the original budget. The cost of the Camp Nou project soared to 900 million euros, far exceeding the original 420 million euros. The cost of the new Batu Blaugrana Pavilion and surrounding facilities has increased from 90 million euros to 420 million euros. Even the regional planning allocation has been increased by an astonishing amount from 20 million euros to 100 million euros.

Four years later, the revised plan was postponed again and funds continued to flow out: 106 million euros were invested in the 22/23 season, which increased to 322 million euros the following year, and another 415 million euros were invested last season. As of June 2025, project capital expenditure has reached 975 million euros (see figure below). Follow-up investment will still be huge.

Barcelona's expenditure far exceeded the original plan

The completion date is far away. The renovated Camp Nou was originally scheduled to be largely completed by the beginning of this season, but Barcelona is still working hard to even partially open it. The first two home games of La Liga this season were forced to be arranged in the small Cruyff Stadium, and then moved to the Montjuïc Olympic Stadium, the temporary home that hosted the 1992 Olympic Games. Last week, the club announced that it would hold an open training session at Camp Nou this Friday, with a maximum capacity of 23,000 fans, "as part of the gradual reopening of stadiums."

Delay will only exacerbate the financial impact. Camp Nou plans to spend nearly 1 billion euros, which does not include the loss of income caused by moving away from the home stadium. The attendance at Montjuïc Stadium is only about half of the 83,000 average of Camp Nou in the 2022/23 season, and every postponement has delayed the rebound of Barcelona's revenue.

The club claims that the Camp Nou plan will eventually bring in annual revenue of 250 million euros. This money is crucial, not only for daily operations, but also for reimbursing the project's own costs. The impact of the project on the balance sheet was significant, and Laporta even persuaded members to temporarily cancel Article 67 of the club's charter regarding the debt ceiling.

Just as leverage was needed to cope with huge operating losses (in lieu of capital injections from the owners), they also had to find other ways to pay the growing bills of the Camp Nou program.

The answer is large-scale lending.

In 2018, Barcelona’s debt was only 67.2 million euros. Although the first 40 million euros were borrowed in connection with the Camp Nou plan next season, the club's borrowing volume increased significantly. In the 18/19 season, another 160 million euros in debt unrelated to the project was added. The epidemic hit the following year, hitting a hole in the already burdened finances.

Shortly after football was suspended, Barcelona used 117.8 million euros of previously unused short-term financing lines. By June 2021, the club had an urgent need for funds, and even applied to Goldman Sachs for a bridge loan of 80 million euros to "pay all bills that must be paid in the next three months (such as wages, utility bills, taxes, etc.)." In the same month, members were requested to approve a 525 million euro debt restructuring with Goldman Sachs, and the final total loan amount obtained from the US-funded institution reached 595 million euros.

This loan takes about 30 million euros from the club for repayment every year, and a one-time payment of 265.7 million euros is required in the 2031/32 season. The interest rate is unknown but expected to be low; Barcelona announced a target interest rate of 3%.

With the addition of 907.7 million euros in Camp Nou plan debt and other sporadic borrowings, the total debt reaches 1.45 billion euros - the highest in world football.

As the project continues, this number will only increase.

Even determining debt figures is not easy.

A year ago, Barcelona's total debt was reported at 1.81 billion euros and was widely reported. Two years ago it was 1.62 billion. Why has the latest figure dropped to 1.45 billion at a time when the cost of the Camp Nou project is rising?

The answer lies in accounting changes.

The Camp Nou plan debt is held by a securitization fund established in 2023 specifically for project financing.. In short, the fund mainly raises funds through bond issuance and then lends it to Barcelona for construction. The return is to repay the loan in the future through additional revenue from the renovation of the Camp Nou.

该基金原被视为受巴萨控制,故其资产与负债纳入合并报表。 But the fund's activities are not limited to blood transfusions into the club. In the early days of its establishment, it raised more than 1 billion euros in debt, far more than Barcelona needed at the time.

Last season’s debt figures therefore include all borrowings from securitization funds, whether or not they have been on-lent to clubs.

This time, the new auditor determined that Barcelona does not actually control the fund and its assets and liabilities should not be included in the consolidated statements. Therefore, only Barcelona's debt to the fund is included. As this amount is lower than the fund's total borrowings, the debt figure is lower than in FY23/24.

In reality, Barcelona’s debt is still rising. As the cost of the Camp Nou scheme continues to grow towards completion, total fund debt is expected to reappear on the club's books.

Barcelona’s financial problems don’t just bother Spanish regulators. For two consecutive seasons, they have violated UEFA regulations in different ways.

In the 22/23 season, they were punished for incorrect revenue classification and tried to include the proceeds from the first 267 million euros in broadcast rights sales into the break-even assessment. Barcelona appealed this decision and the 500,000 euro fine, but the CAS arbitration panel supported UEFA and believed that the fine was "actually light."

Even excluding the 267 million euro transaction, Barcelona still barely met the break-even requirement in the quarter, partly due to epidemic-related adjustments. But the situation changed a year later. UEFA was more stringent on leverage operations than La Liga. Barcelona exceeded the standard in the first year of the implementation of the new "football revenue" regulations. For this reason, they were fined an additional 15 million euros and reached a two-year settlement agreement with UEFA.

Subsequent financial penalties may follow. If Barcelona exceeds the agreed football revenue target this season or next season, it will be fined up to 22.5 million euros per year - and this is limited to an excess of no more than 20 million euros. If the limit exceeds 20 million euros in any year, it will be regarded as a violation of the settlement agreement and will be banned from European competition for one year.

Barcelona recorded another loss in the 24/25 season, but the amount of 8.4 million euros was significantly narrower than in previous years. This includes €71.6 million in PSL revenue (which is likely to be non-repeatable), but will be offset by continued gains from the Camp Nou restart - whenever that happens.

Football costs were once a chronic problem for Barcelona. Although they increased to 471.4 million euros (salary plus amortization) last year, they have dropped by more than 120 million euros from the terrifying peak in 2019. Combined with revenue returning to growth, the club achieved an operating profit (€72.1 million) for the first time in eight years. The proportion of wages in income fell to 52%, the lowest in 12 years.

Revenue growth was mainly driven by the surge in commercial revenue. Although Bartomeu's era was famous for his profligacy, he achieved outstanding results in commercial development. During the five years of his administration to before the epidemic, this revenue stream doubled, partly due to the establishment of BLM in the 18/19 season to bring the retail business back to self-operation.

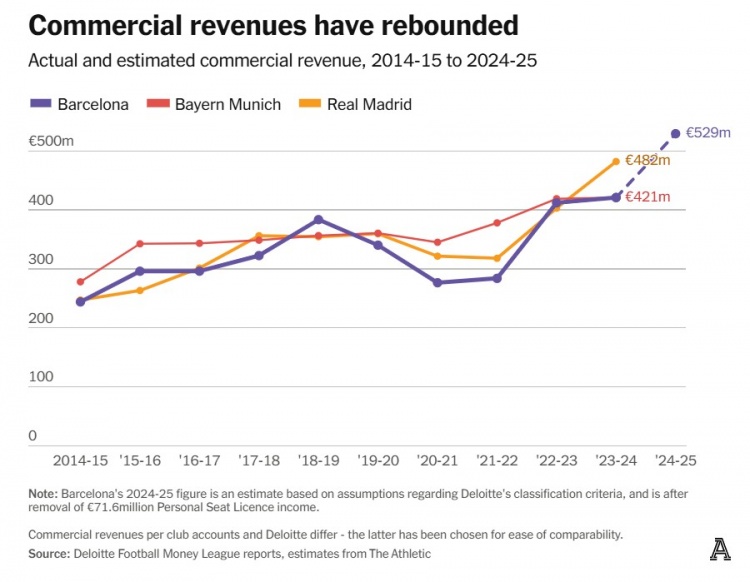

Barcelona's commercial revenue has gradually recovered

The growth continues. Barcelona includes PSL revenue as a commercial item, but even if it is treated as a one-time gain and excluded, according to Deloitte's estimates, its commercial revenue may still exceed 500 million euros.

This is due to large-scale cooperation with global brands. The renewed contract with Nike will earn an annual income of 108 million euros, which will rise to 120 million in 2028. The contract also includes a signing bonus of 158 million euros. Spotify, the sponsor of the Camp Nou naming rights and chest advertising, pays 55 million euros per year. The BLM business has made substantial contributions.

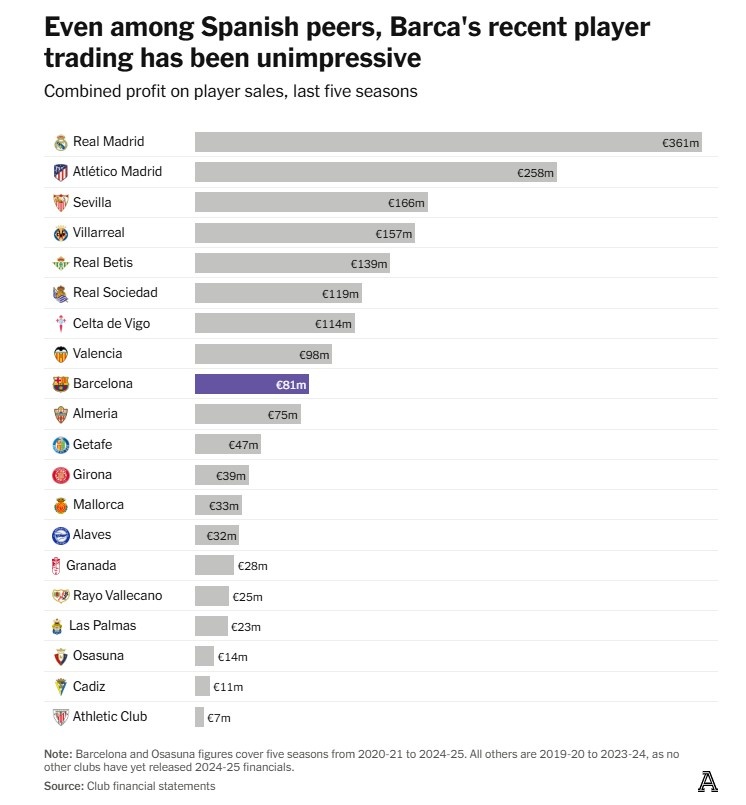

On the other hand, despite financial improvements, player sales revenue has declined, contrary to the Bartomeu era. The sky-high sale of Neymar should have led to rational signings, but instead started a cycle of disastrous spending, even though selling people was once a healthy source of income. From 2017 to 2020, Barcelona recorded a player trading profit of 376.9 million euros, which happened to offset an operating loss of 432.3 million euros during the same period.

Since then, the profits from selling have shrunk, even in the 23/24 season, a profit of 80.6 million euros was made from the sale of Dembele, Kessie and Nico Gonzalez. The total profit from player sales in the past five seasons was only 81.4 million euros. If it were not for the 160 million euros impairment of player value in the 21/22 season, the figures would be even more ugly. This profit level is in the middle of La Liga, far behind the two Madrid clubs and many European rivals.

Even in the internal comparison of La Liga, Barcelona's recent player transactions have been mediocre.

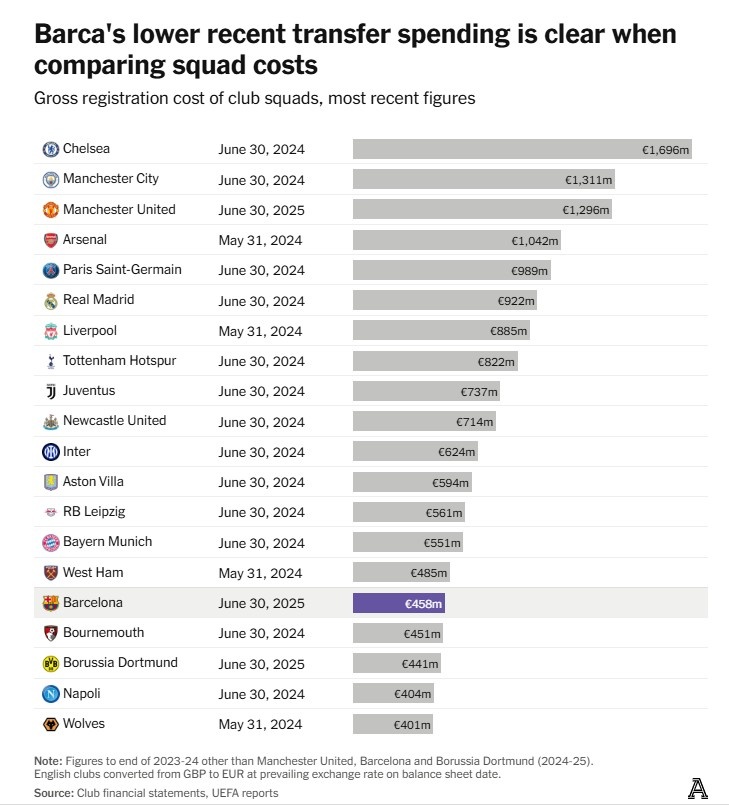

Transfer spending has dropped during Laporta's tenure, at least since the introduction of Raphinha, Konde and Lewandowski in the summer window of 2022. The net expenditure over the past two seasons was only 3.9 million euros. Net spending was roughly flat in the summer window that just ended, despite the high wages involved in bringing Rashford on loan from Manchester United.

Reducing expenditure has become the norm, even though Barcelona's decisions still sometimes violate the original intention of returning to stability.

The farce of Dani Olmo last summer is clear evidence.

This new player introduced from Leipzig for 60 million euros, like the 2022 trio, was unable to register after signing. In the end, he was allowed to play in the first half of the season due to the long-term injury of new teammate Christensen. The following January, due to La Liga questioning the club's confirmation of VIP seat revenue, Olmo and new aid Victor only completed the registration after the relevant departments intervened.

Despite the reduction in transfer spending, Barcelona's net transfer debt of 81.7 million euros as of the end of June is still the highest in La Liga, reflecting the tightening of spending by other teams in the league. They still owe Raphinha 42.3 million euros, Olmo 33.7 million euros, Kounde 25 million euros, as well as Roque 17.2 million euros, Ferran Torres 13.8 million euros and Lewandowski 11.3 million euros. A net transfer installment of 100.2 million euros needs to be paid this season (a net receivable of 18.5 million euros in future seasons), putting further pressure on short-term cash flow.

When comparing team costs, Barcelona's recent low transfer expenditure is obvious

Even with signings such as Olmo, Barcelona's lineup cost at the end of June still ranked outside the top 15 in the world.. The player's book value is even lower, only 188.9 million euros, but the club emphasized in its latest statement that this figure is incomparable with the realization potential of the modern transfer market.

Barcelona claims that "the value of (the lineup) exceeds the net book value by more than 1 billion euros." Although this is a subjective judgment, it is not far from the truth. La Masia youth training gems such as Yamal, Garvey, Fermin Lopez, Balde and Kubalsi have extremely low book values and will receive sky-high transfer fees if sold. Yamal’s market valuation alone has been regularly assessed by many institutions to exceed 300 million euros.

Confirming market value may improve financial image, but may weaken competitiveness - and the reluctance to sell stars is part of the reason for embarking on the path to leverage in the first place.

Retain low-cost players to control transfer expenditures, but the other side is that these players know their own value and demand corresponding treatment. Barcelona's football wage bill is rising again, with an increase of 26.3 million euros (7%) last season. Only the last month of Yamal's new contract (with an annual value of up to 40 million euros) is included in last season's data, so it is not surprising that wages will increase again this year.

Barcelona remains a mystery.

In other industries or clubs, drastically cutting costs and saying goodbye to financial spending should be the top priority. But in Catalonia, under the leadership of Laporta, whose popularity is related to the longevity of his rule, Barcelona chose to continue to seek novel financing methods. Laporta faces the 2026 election, and the recognition of his decision-making will be determined. As long as his record does not collapse by then, he is expected to be re-elected.

Barcelona’s transfer spending has been under control in recent years, but wages remain high in order to retain new stars. Based on the latest data, the salary bill of 510 million euros for the 24/25 season is second only to Paris and Manchester City in Europe, but this also includes the cost of supporting athletes from other sports and a large team of off-field staff.

We are far from returning to normalcy.

Last season, even if the core indicators rebounded, Barcelona's finances still had enough room for explanation, causing the club to change auditors twice.

They did not renew Grant Thornton's contract, and Crowe audited the 24/25 fiscal year statements. There was also the brief intervention of an undisclosed third audit agency, which is believed to be related to Barcelona's attempt to fully confirm PSL revenue. Although "As" reported that it was Abauding, a local firm in Barcelona, the identity was never officially announced, and Abauding did not respond to the newspaper's request for confirmation.

Frequent changes of auditors are hardly a good omen.

The same goes for the extensive restatements of data in the latest reports.

It is not unique to retell past data, but Barcelona has frequently looked back in recent years, reflecting the club's trajectory of finding unconventional means to escape difficulties for many years.

Even if the revenue for the 25/26 season is forecast to exceed 1 billion euros, they are still stuck in the dilemma of La Liga rules this summer. In August, Laporta's board of directors used his personal assets as collateral to borrow 7 million euros to increase the SCL limit in order to register Rashford and new goalkeeper Joan Garcia before the new season.

It is crucial to fully restart Camp Nou as soon as possible.

Mounting debt is not a problem in itself, but past financial trauma has shaken confidence in the future. The recent restructuring of the planned 424 million euros of debt at Camp Nou has reduced the average interest rate to 5.19%, but is still two points higher than the 3.2% of Real Madrid's stadium debt. Such a high amount of debt will take decades to repay, and higher interest rates will affect Barcelona's competitiveness with its old rivals at the Santiago Bernabeu.

It is too early to conclude that Barcelona has completely escaped from the abyss a few years ago.

The extension of Camp Nou is a sign of inefficient operations. The battle for domestic and international compliance continues. Short-term liabilities remain much higher than assets. Overall profitability is nowhere in sight. The club continues to seek unconventional financing; the attraction of the recently canceled Barcelona-Villarreal Miami game is the potential revenue generation.

Yet Laporta's gamble is paying off on several levels.

On the field, Barcelona returned to competition and renewed passion. Under Flick's training, they have a valuable young guard. The lesson is obvious, just like it was twenty years ago: trusting youth training is far better than spending money on signings.

The latter nearly destroyed them.

The journey from confusion to awakening is still exciting.

"Not just a club"? If you are honest, I won’t deceive you.

Mini-game recommendations:Castle Defender Saga